Did you know that there are deep-sea coral reefs in Irish waters? Not many people know that there are corals hundreds to thousands of metres underwater. These corals form huge reefs and gardens and support a diverse range of commercial fish species. Unlike tropical coral reefs, they do not have the symbiotic zooxanthellae to feed, but instead feed on matter sinking from the surface. Meet Declan Morrissey, a marine biologist in Galway studying slow growing deep-sea corals!

Declan grew up exploring rock pools in Kilkee Co. Clare where he became fascinated by the sea stars, fish, shrimps, sea urchins and multitude of other marine organisms. Like many, he is also a devout follower of Sir David Attenborough, and between these two exposures to the natural world his interests led him to study marine biology at university. He maintains these interests outside of his work too through jogging and local nature reserves near his home.

Declan says he … “thought it [marine biology] would be all about studying whales, dolphins, turtles and fieldwork in hot countries [and] didn’t realise there was such a broad umbrella within marine biology.” He’s had many amazing opportunities throughout his university experience, including spending time at sea on research vessels. During these trips he has been able to assist in the collection of specimens for his own research and learnt from experts in the fields of deep-sea biology, taxonomy, and seafloor mapping. His learning has taken him around the world, spending time at laboratories in Iceland, the UK, and Portugal.

Currently obtaining his PhD, Declan works on DNA sequencing his corals. Through a process of heating, and adding a series of other substances, the order of chemical bases creating a species’ DNA can be determined. This helps scientists understand why the species may show, or lack, specific traits. While it requires expensive lab equipment to decipher a coral’s genetic make-up, Declan in fact works at a computer most of the time. The marine science taking place at sea or in a lab is like the exciting cover to a slightly less adventurous book. After collecting and processing physical samples and data, that information has to be analysed. This is usually done through comparisons with other sets of data and using statistical functions to try and determine whether or not the results are reliable or just a coincidence. It also involves a lot of technical reading to brush up on similar studies and background information so that when it comes to writing up one’s own research – putting the study down on paper – it’s backed up by the work of other experts in the field.

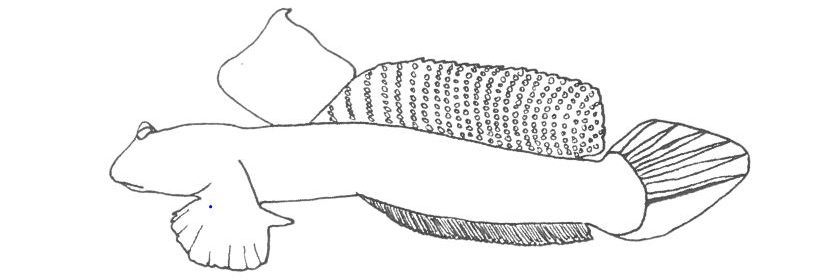

Bamboo corals, Declan’s research focus, have a distinct banded pattern which is where they get their names. However, other characteristics such as branching pattern and colony shape can be unreliable in identifying species. This is because certain traits work well for life in the deep-sea and thus have evolved multiple times. His research focuses on correctly identifying species that may look the same, but in fact are very different. While looking at the structure and shape of corals he also combines this information with the variation found in their DNA. Even using both methods together there are still a lot of unknowns around biodiversity of deep-sea corals in Ireland. No one’s ever said a coral is a particularly mobile organism and scientists are still trying to understand how species which appear similar can evolve thousands of miles away from one another. This unknown is amplified in deep-sea research because the depths of our oceans are even more difficult for humans to access than the surface. The element of the unknown was something which drew Declan to deep-sea research in the first place. “My motivation is the chance to reduce the number of times someone utters ‘I don’t know’ in relation to the deep sea.” He’s found that at the moment staying in the world of academics is the way to accomplish that.

One of the skills Declan says he uses most frequently is that of patience. Science can be a fickle thing and experiments are often accompanied by waiting for results, comments and feedback, or funding decisions. Success is never a given and a lot of scientific experiments fail, or hypotheses aren’t proven. Seeing the long-term goal and road map definitely helps get through times which feel like complete failure. Alongside the ups and downs of science, researchers are constantly having to learn new skills so that they can stay at the forefront of their field. In the lab Declan may wear the hat of ‘biologist’ and ‘geneticist.’ At his computer he currently wears the hat of ‘writer’ and ‘programmer’ while he learns Unix and Python. This process in itself can throw new and challenging problems to solve at a researcher.

“Science is not a route you can take alone” says Declan. It’s fraught not only with scientific challenges, but the challenges presented through being an academic, such as finances. Having a support network inside and outside the lab is really important. Everyone needs a cheerleader, and everyone needs a shoulder to lean on. I met Declan through a mutual frustration with Flixbus while waiting at a bus stop in Bremen. We both happened to be headed for a marine ecological summer school in northern Germany. I promptly abandoned him when the bus showed up two hours late – I had a ticket, he did not – but it was the start of a great marine biology based friendship and I hope I have since been a better cheerleader and shoulder to lean on.

There are many factors which determine what we are interested in and how we end up studying or working in a certain field. However, it’s important to remember that, like Declan didn’t know all the possibilities within marine science when he decided to study, there’s always more for us to learn. He says that despite the idea that it may be impolite to ask for things and to never cause a fuss, he wouldn’t be the researcher, and person he is today if he hadn’t stuck his neck out and asked for what he wanted. Keep exploring, learning, and asking!

If you’d like to learn more about Declan’s work you can visit his website www.declanmorrissey.com or follow him on twitter @squidblubber.

Acknowledgements:

Declan Morrissey is a PhD student in the School of Natural Sciences at NUI Galway. His research project “Deep OCEAN” (Deep-sea Octocoral Evolution, Connectivity, and Associations in the North Atlantic) is funded by the Irish Research Council postgraduate scholarship scheme and is supervised by Prof. Louise Allcock.

Prof Louise Allcock is the PI of the Science Foundation of Ireland Grant “Exploiting and conserving Deep-sea genetic resources”. She is the Head of Zoology at the National University of Ireland Galway. For more information about this project you an visit http://marinescience.ie/summary-sfi-project-exploiting-and-conserving-deep-sea-genetic-resources/. All the images used in this article were taken aboard the RV Celtic Explorer. The images were taken during research cruises on the RV Celtic Explorer in 2017 and 2018. These cruises were funded by Prof Allcock’s SFI project “Exploiting and conserving Deep-sea genetic resources”. Thus all images are credited to Prof Allcock, the Marine Institute, Science Foundation Ireland, NUI Galway, and the Ryan Institute. Images of the corals were taken with the Holland I, Ireland’s Remotely Operated Vehicle.