It was very calm. The humidity draped around me like a blanket, and I looked off the stern into the darkness. It was like a black velvet curtain. Nothing was there. And then a glimmer, a passing ship, a twinkling star. A few minutes passed, all was well with the equipment ticking away off the starboard side. I turned and and went back to the lab, the door clanging behind me.

I use to be indifferent to boats. I used to hate boats. I now love boats. I have a few distinct memories of my first watery vessel forays. My dad took me sailing on a lake when I was about 3 years old. There was no wind and we sat in the middle of the pond for a while and then drifted to shore. Scintillating, let me tell you. A few years later, while visiting friends in Vermont, I decided I was petrified of stepping foot on their catamaran. Consequently, I was left to sulk, while everyone else had fun. There was also a particularly memorable canoe trip along an English canal. I whined the entire day, there and back. I utterly pissed off my parents, until we returned the boat when I promptly said “that was fun, can we do it again?”

I’m not sure when I decided that boats weren’t all bad, but I did. As a teen I loved my summers sailing at camp and would have happily sailed all day everyday. I think my skin’s affinity to sunburn was more of a limiting factor. I even bought a sailboat. Not the most well thought through financial decision, given that I lived two and half hours from the nearest coast, but even slow jaunts around a tiny local lake were enjoyable.

After my transformative childhood, and as an oceanographer, I wanted to be a research cruise participant. Nothing was more exciting than the thought of spending an extended period of time on a boat, at sea, doing marine science, with other scientists. This dream however, came with a slight snag: it’s really difficult to get on a research cruise.

For me, the ultimate oceanography achievement has always been fieldwork, and more specifically, as I learnt more about research methods, fieldwork at sea. However, boats are expensive, they don’t travel very fast compared to the distances scientists want to travel, and they are physically limited in space for people and equipment. This severely restricts who can come. As a student you have to know the right lecturers, be part of the right project, and play the right role in the project, to participate in fieldwork at sea. That didn’t happen for me. I sat in a lab peering at rice grain-sized crustaceans for nine months. Don’t get me wrong, it was great, but it wasn’t a research cruise.

I thought I would have to wait until I was next working at a university in a marine department, playing a key role in a project requiring sea-based fieldwork. Thankfully I was wrong. I discovered that the University-National Oceanographic Laboratory System – a group of organisations in the USA which coordinate research vessel activities – offer up spare bunks to graduates. I was lucky enough to apply and be chosen as a volunteer on the Research Vessel (RV) Endeavor operating out of the University of Rhode Island.

In October of 2018 I embarked on some of the most fulfilling weeks of my life. Career goals coming true, I might have thought that the eastern seaboard of the US wasn’t the most exciting location for a first research experience at sea, but what I learnt was that it doesn’t matter where you spend your first research cruise, it’ll still be an amazing experience. While I liked to think that I had spent time on boats, scientific boats even, and wasn’t concerned about being at sea, in reality I had no idea if my sea legs would kick in. Added to which, when we left the pier, I was surrounded by people I had only known for about 24 hours.

Turns out my sea legs did kick in despite the rough weather, and my 24-hour friends turned into 504+ hour friends. Working 12 hour shifts, in my case 12pm to 12am was exhausting at times, but I found that I would still want to stay up watching the action into the wee hours of the morning. I learnt mountains about acoustic sampling and western Atlantic ecology all from being in the thick of things. I also managed to get through seven books due to the long transit days and rough weather, stalling our activities. I soon ran out of my own reading material and moved on to the incredibly well-stocked ship’s library. During other lull periods we played all manner of games, ate, and slept.

Sleeping was a mixed bag in my bunk. During rough weather, trying to brace myself into the bunk made sleep almost impossible. In contrast, on calm days the rocking put me to sleep instantly. Below the water line with no port hole, my altered sleep patterns weren’t interrupted by sunrise or sunset…just the incessant lapping of the ocean and sloshing of the water tank below the stateroom. Below decks the temperature stayed nice and cool, even down near the Florida coast. One of the more unexpected occurrences however, was when my room became significantly warmer than it had been and it dawned on me that we had entered the Gulf Stream, and therefore the warm waters sweeping up from Mexico were also warming the ship.

On a few occasions I attempted to exercise. It turns out that even on a stationary bike, three miles is very, very difficult on a boat. Picture cycling up and down a skate park, except you can’t see where downhill becomes uphill…and you aren’t actually moving anywhere. Similarly, showering was a balance challenge. Thankfully I never fell on my face, but washing my hair became a well-calculated procedure.

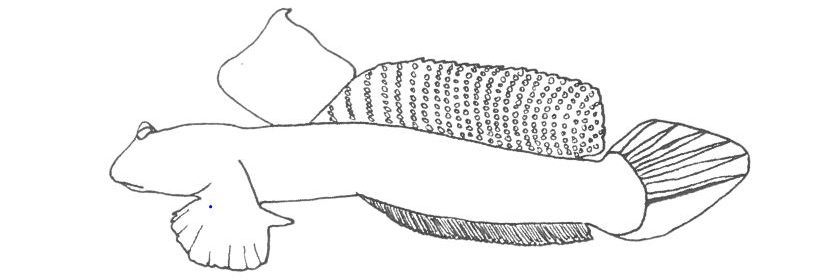

As my time on the Endeavor came to a close I was eager to be inducted into the Secret Salp Sucking Society. For those who don’t know, a salp is a tunicate. While not at all related to jellyfish, they do resemble them. Now the key requirement for an induction is of course the presence of salps, and when we hit our seventh site we were in luck. Salps galore! After choosing a small, inoffensive specimen, I was asked to recite a few words and then gulp it down. It was chased by apple pie and I will never look at a salp the same way again.

Beyond bizarre open ocean rituals, the final few days included shrinking Styrofoam cups at 2000m below the surface, playful dolphins, securing equipment, and horrendous weather. I did discover that my stomach’s weak point is when sat on a spinning chair in choppy seas and even though I should have known, the open ocean is not all windy and chilly like UK waters. When you go south, it gets warm and humid, surprise, surprise.

We were greeted by a satisfying amount of snow the evening we returned to shore and as we stumbled on sea legs and beer through town, I felt nothing but satisfaction with my first offshore experience. It was an experience from which I expected great things, but had no specific expectations; a rare experience which could have only been enjoyable. I feel more like an oceanographer and more excited for the seagoing possibilities in my future.